Years ago, I was in a therapy session trying to make sense of my foster care upbringing. I entered the system when I was three years old after being abandoned on the public metro bus when my father was arrested for being drunk. What I wished to be a short stay in that emergency foster home turned into thirteen years.

The relationship with my guardian was complicated. Through therapy, I came to terms with the fact that someone who undoubtedly loved me as her son could also be the person I held accountable for the trauma I was trying to overcome.

During one particular session, the therapist was eager to give me an assignment that he thought could help me better understand myself.

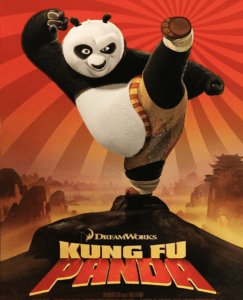

Lesson Learned From Kung Fu Panda

A couple of days after this session, I bought tickets to watch Kung Fu Panda. While I found myself entertained by Po’s bumbling methods of mastering kung fu, I was intrigued by the connection the therapist wanted me to make between the movie and my childhood.

As explained, the villainous snow leopard, Tai Lung, inability to come to terms with being denied the title of Dragon Warrior caused him to become a monster who was feared by all. The source of Tai Lung’s yearning to become the Dragon Warrior was his adoptive father, Master Shifu. Master Shifu nurtured Tai Lung’s ambition since childhood and, as a parent, failed to reign in Tai Lung’s lust for power. Master Shifu’s complicit role in feeding Tai Lung’s thirst for total power as the Dragon Warrior led Tai Lung to prison where he eventually escaped to wage war against Po but really it was a war against his father and his inner-wounded cub.

This innovative approach by my therapist to help me understand my trauma did in a couple of hours what he’d been trying to help me understand for a couple of months. Due to this single session, I’ve leaned on the Kung Fu Panda franchise to help PJ understand my origin story (perhaps I’ll blog about that later). The point of this blog, however, is to share how I leaned on a similar method when PJ was a toddler to help him understand emotions.

My therapy experience has been key to my evolution as a man and father. It helped me realize that for most of my life I lacked emotional awareness because I never acquired an emotional vocabulary as a child. Up to the point of therapy, I lived a numbed existence.

Who wants to feel perpetual pain from being abandoned by both parents?

I didn’t want to relive those feelings of rejection by my guardian whenever I went astray from her expectations of me as a child.

I mean, as a father, I know my son is going to deviate from my expectations. Yet, I know it’s my role to correct him from a place of compassion so he learns the error of his ways.

From therapy, I learned that by numbing myself to the pain, I was numbing myself to the joys of life too. This existence stunted my emotional development. And such awareness, especially once I knew I was going to become a father to a son, motivated me to build on all those years of therapy, gratitude journaling, and meditating by embracing a conscious parenting philosophy to how I wanted to raise PJ.

Avoiding the Sins of the Father

One of my first goals as a father was to help PJ acquire emotional awareness ever since he was a tiny lad. I wanted him to experience the richness of life through his ability to access a robust emotional vocabulary.

Embedded in my goal was the understanding that my primary role was to aid PJ through understanding how he could manage his feelings during his formative years.

The more I researched what it meant to be a conscious father, the more I understood the need to counter the Boy Code. The Boy Code, as described in William Pollack’s, Ph.D. Real Boys: Rescuing Our Sons from the Myth of Boyhood is “the culturally ingrained code of acceptable behavior that dictates what boys can feel and what they cannot”.

One apparent cliche from the world of sports that has a broader cultural significance for fathers of sons is “there’s no crying in baseball.” Perhaps there’s not a place for crying in baseball or any sport, however, I do believe there’s a space for processing the range of emotions that can develop on the baseball field that’s transferable to our sons’ various relationships.

To me, there’s a space for leaning into Spock mode where my son needs to use logic and reason to make a decision. But relying on Spock mode as the sole basis for processing life when we are emotional beings, well, that’s not something I can embrace.

Current research indicates that emotion is what connects various parts of our brain and it is through this neural connection that people develop into healthy individuals. As a result, I’ve focused on helping PJ identify how he’s feeling and how to express those emotions for as long as I can remember.

Using emotional vocabulary when PJ was still a babbling baby was vital to exposing him to the language. As he began speaking more, I started sharing more of how I felt at a given moment. For example, as we overlooked the pacific ocean on top of the Santa Monica Pier, I’d describe how excited I felt seeing the beautiful ocean horizon with him! From there I’d ask how he felt. Then I’d ask why to encourage him to articulate why he felt a given way. So the model was:

My Feelings —> Why I Felt That Way

His Feelings —> Why He Felt That Way

Experiencing and Expressing Emotions

One of my fondest memories occurred when I took a four-year-old PJ to a birthday party. At that time, we were officially together from Friday to Monday morning, every other weekend. This visitation schedule resulted in PJ wanting to always be by my side. If we were at a park and another kiddo came up to play, he’d grab my hand and say, “Com’on, Papa, let’s go here” and he’d walk me somewhere to play hide and seek or maybe tag.

That day we arrived at the party early and I’d managed to convince PJ to join another boy in a bouncy house. I used the moment to ease away so he’d grow more comfortable playing with the other boy. Eventually, I heard PJ call for me. As I approached closer, I heard the boys bickering.

The agitator was mocking PJ’s calls for me. For every call of “PaaaPa” made by my son, the other boy would mimic him.

Then I surprisingly heard PJ declare, “He’s MY PAPA!”

Once I caught PJ’s attention, he asked to leave the bouncy house. Even though the look on his face was that of anger, I still asked him who was looking through his eyes at that moment.

PJ shared that anger was looking through his eyes.

When I asked why, PJ explained the obvious – because I was his papa!

I used the moment to help PJ understand that his feeling was justified. I didn’t want him to feel shame by telling him he was wrong for how he reacted. I also explained that I thought it was awesome that he used his words to express how he felt. Basically, I was trying to reinforce the understanding that how he handled the situation was okay without guilt-tripping him for how he reacted. Like, I didn’t want to give the “Well, of course, I am your father, why are you letting that boy bother you” spiel.

It was important that PJ’s feelings were honored at that moment. If he felt it was important enough to stand his ground to that older boy, then he needed to know that I stood beside him.

Having gone through years of therapy, I’ve learned that anger is often a secondary emotion to another primary feeling. So when PJ angrily responded to the boy calling me “Papa”, I used it as an opportunity to comfort him by reminding him that I’m, indeed, his father and that he’s my only son as I carried him away.

Although he didn’t quite have the language to delve into why he felt angry, I sense it came from a place of anxiety due to his longing for more time with his father.

After soothing his feelings, I leveraged the moment to ask PJ who was looking through his eyes.

“Joy, papa.”

Who’s Looking Through Your Eyes

Never could I imagine that the Kung Fu Panda experience would pay off years later as I thought about how I could help PJ develop an emotional vocabulary foundation. With the release of Pixar’s Inside Out, I knew this movie would play a pivotal role in achieving my goal.

One Saturday evening I decided it was time to show PJ Inside Out. Days prior to movie night PJ’s preschool allowed me to volunteer for a field trip to a local wildlife rescue center.

During a Show and Tell session, a staff member held a boa snake and asked the kiddos why they think a snake hisses.

PJ had been eagerly raising his hands to ask questions throughout the morning and did so to answer this question. His answer escapes me now but the feeling of that moment was just pure innocence and caused us to laugh in pure delight. For PJ, our laughter was processed as laughter at him or ridicule towards him. I remember how quickly my mood changed from joy to concern as I noticed tears welling up in PJ’s eyes. Instinctively, I discreetly placed a kiss on his cheek and rubbed his chest to soothe him in a manner to not bring any unwanted attention to him.

Of course, when the moment was appropriate I tried explaining to PJ that we weren’t laughing at him but we were amused by the sweetness of his innocent answer. Despite assuaging his feelings at that moment, I knew a longer-term solution was needed. I believed for him to process how he felt about an experience, his four-year-old self needed a framework for expressing his feelings.

And that’s where Inside Out came in.

Movie Night

Immediately after watching Pixar’s Inside Out, I knew this movie would play a pivotal role in helping PJ acquire an emotional language foundation.

The process was simple. It involved simply watching the movie multiple times and asking more and more questions with each viewing session. I knew this would be a rinse and repeat approach until the core concepts of the movie were ingrained in PJ.

I cannot begin to express just how rich of a relationship we have together as a result of this experiment turned lifelong lesson.

The language of “Who’s looking through your eyes right now” is a core part of so many of our experiences together.

I saw the fruits of our labor on full display the first time my son saw me cry. PJ was three and a half when his beloved great-grandma passed. His great-grandma was a woman I met in 1996 after my foster grandma of 13 years died. Among all of the people who shared their condolences with me on that Sunday morning was a little woman who waited until it was just the both of us. With compassion in her eyes, she said, “You don’t know me, but I’ve seen you since you were a little boy. I watched you singing in the choir. I watched you as a little acolyte lighting the candle before worship. If you’d let me, I’d like to introduce you to my daughter. May I?”

From that short conversation, we embarked on a 23-year-long journey. Her family became my family. Then PJ’s family. And PJ only knew her as his Grandma Gigi.

Shortly before Grandma Gigi’s passing, I was anxiously laying in bed with him. Weighing on me was the recognition that I needed to explain what was happening. Only when PJ expressed concern for his ailing fish did I recognize the opportunity to initiate the conversation.

Our conversation was emotional for me. To help him process my feelings, I asked who did he think was looking through my eyes?

PJ said, “Sadness and Joy” because of everything that Grandma GG did for me.

I could tell he was understanding the nuance of emotions. Specifically, that emotion need not be a singular experience but could be informed by other emotions. PJ understood that I was sad because of all the joy that Grandma Gigi and her family brought into our lives and sad because she was no longer with us. At that moment, I knew I’d discovered a way to help him understand and express his emotions.

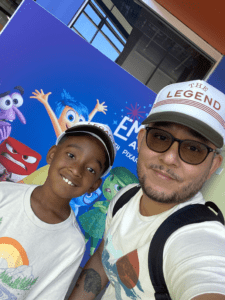

PIXAR’s Inside Out Exhibit

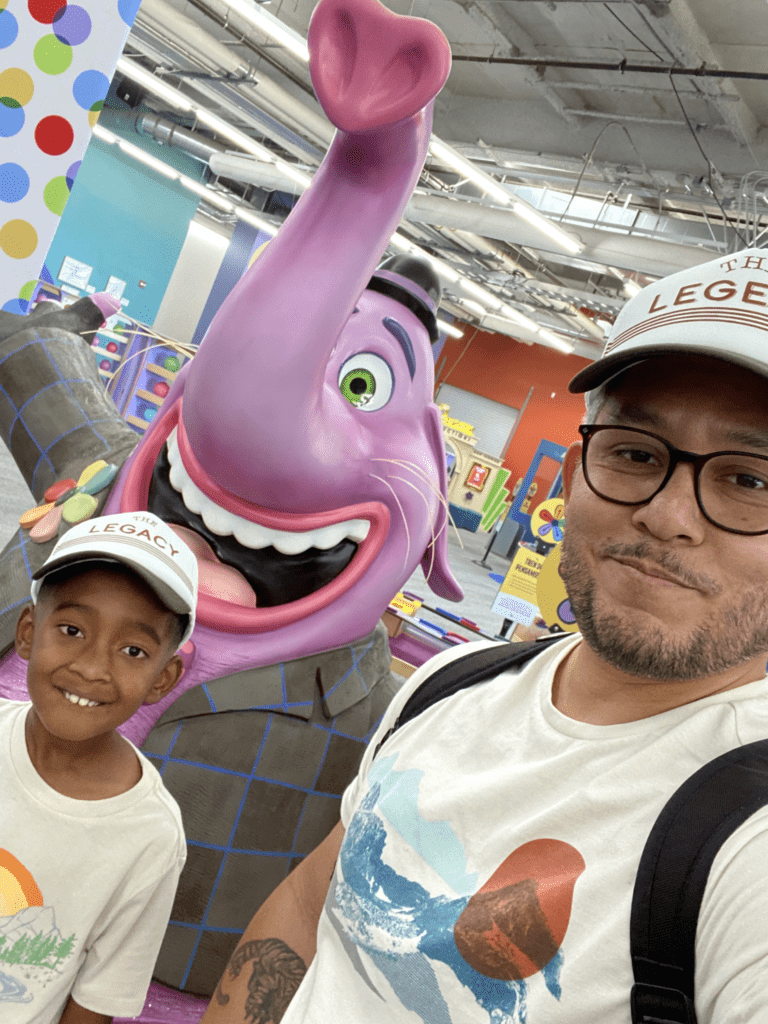

When the Discovery Cube began advertising the Inside Out exhibit, family and friends began notifying me about it. Little did they know I’d bought tickets for Father’s Day 2022. I thought it’d be awesome for us to see how all of our years of learning about our emotions by relying on the movie would translate into a fully interactive experience.

When we arrived at the Discovery Cube, I pulled out our Legend and Legacy hats that were gifted to us. With the hats on, we entered the facility and to PJ’s delight, he pointed to the Inside Out signage that adorned the walls.

PJ was all smiles and excited as he saw Bing Bong standing at the entrance of the exhibit. As PJ slowly walked inside, I followed behind him as he looked in awe at the various feeling stations that resembled so much of what we loved from the movie.

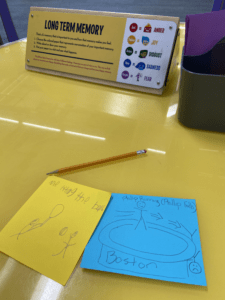

The first station we visited was the Long Term Memory station. Here we were instructed to think of a memory that happened a long time ago. Then we had to use a color sheet of paper that resembled the feelings from the movie: Yellow-Joy, Blue-Sad, Purple-Fear, Red-Anger, and Green-Disgust. On the paper, we could draw or write out the memory. For PJ, he drew a picture of him hitting a baseball on a yellow sheet of paper. For me, I drew a picture of PJ falling off of a circular water fountain that he was running on during our trip to Boston. After we finished our drawings we shared why the memories mattered to us. From there, we slipped the paper into a slot that projected light through the paper which in turn illuminated the balls the same color as the paper. The colored balls represented the crystal memory balls from the movie. When PJ saw the balls change colors, he shrieked in delight.

The Emotions In Motion station was by far my favorite. Lately, when I asked PJ how he feels about a given experience he’ll attempt to deflect the questions to something else. I’ve started noticing this with experiences that might be a tad bit sad for him. Like when we watched E.T. for the first time, he preferred to just cuddle with me rather than vocalize how he felt. When I noticed how captivated PJ was by the station, I decided to use it as an opportunity to gauge how he felt about certain experiences.

“How do you feel now that summer is here?” PJ turned the emotion dial to sadness so the ball would turn blue once it was placed in the machine. For Phillip, summer meant he couldn’t see his friends at school.

“How do you feel being a Dodgers fan?” Yellow-Joy was selected.

“How do you feel about Papa being an SF Giants fan?” Red-Angry was selected.

Those responses were all I needed to know about what our house-divided life would be like in the future.

PJ and I really found ourselves jamming out at the Control Panel station. The Control Panel station focused on teaching the kiddos how music can generate different types of emotions. Each color on the station represented a sound that could be associated with a particular feeling. PJ loved this station! And I found myself fascinated by the harmonic music he ended up producing. As he spun the digital turntable, moved levers, and tapped on the electronic drum, I found myself wanting to freestyle to the music that PJ was creating. I stood there just nodding my head in total amazement at the fluidity of my emotions based on what PJ was doing.

We left the Discovery Cube with an annual pass simply because that exhibit merited multiple visits. This emotionally enriching Father’s Day experience renewed my commitment to enhancing PJ’s emotional awareness. Even recounting this day reminds me of what I’m learning from reading The Whole-Brain Child. The book explains the necessity of parents speaking to their children about feelings because it helps with their emotional intelligence development. An emotionally intelligent child is one who is attuned to self, their parents, and other people. I’ll get more into what I’m learning from The Whole-Brain Child in a later blog. As of now, I appreciate how the book emphasizes the need for parents to create experiences that help mold our children’s brains so they become more thriving and resilient people.

The Inside Out exhibit at the Los Angeles Discovery Cube set the stage for a summer of emotional exploration and emotional growth that I’m excited to experience with my amazing son!